Beneath the veneer

By John Hendry

One of the most enduring images in the history of European art is also one of the most unassuming. A plumpish serving girl pours a thin steady stream of milk from a jug into a bowl. This is Johannes Vermeer's The Milkmaid. If you want to find out what makes such an apparently modest statement one of the high points of Western culture, then get along quickly to the show Vermeer and the Delft School at the National Gallery.

The show sets out in part to show that Vermeer was no lone genius working apart in seventeenth-century Delft, and indeed, there is an excellent collection of paintings here, including well known names such as Pieter de Hooch and Carel Fabritius. But the key works on display here are those of Vermeer himself. The others, for all their quality, show that Vermeer, at the peak of his powers, was unrivalled in his ability to create the illusion of reality on a flat square of canvas.

A couple of larger early Vermeers illustrate the point just as effectively. Christ in the house of Mary and Martha, painted around 1653, is clearly the work of a master painter, but it has none of the atmosphere, depth of perspective or virtuosity that set the great paintings apart. Some aspects of The Procuress (1656) look distinctly clumsy; the groping hand looks improbably large and the musician on the left seems to have wandered in from an entirely different picture.

For the most part, it's the smaller canvases that set the pulse racing. The Milkmaid, for instance, is about the size of a sheet of A3 paper. On this scale, Vermeer painted a series of quiet indoor scenes, unremarkable for the most part in terms of their content, but stunningly lucid in presenting light, different surface textures and the illusion of depth. Look at the broken bread on the table. Look at the glaze on the jug and the bowl. Look at the cracked plaster and other features on the plain wall behind.

And that's the deal. All this skill has gone into a simple depiction of daily life. The girl is no aristocrat. It is not a great event from history. There is no melodrama, no passion. There is only a serene sense of calm and order that can be witnessed in the other Vermeer interiors here, such as Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, and The Glass of Wine. In the latter, the chance to see the rendering of light coming through the glass of the open window is worth the price of entry alone.

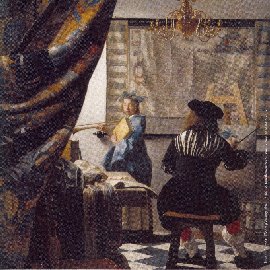

There is one large Vermeer interior that merits special mention. The Art of Painting, which normally hangs in the Kunsthistorisches museum in Vienna, is justly famous, and is the centrepiece in the last room of the exhibition. Vermeer never sold this painting, and may well have used it as a means of proving his skill to prospective patrons.

It's easy to see why. The detailed reproduction of the map on the far wall, complete with bumps and creases, is an extravagant demonstration of that skill. So too are those contrasting gathered folds in the back of the artist’s jacket. The light from the concealed window on the left, the gloom beneath the easel and the drawn-aside curtain are all somehow captured under the veneer.

So where does this leave the rest of the Delft school? Essentially, they are competing for second place, but it's an impressive struggle to witness. There are de Hooch's cool interiors with their tiled floors, and his sunny courtyards, with intricately observed brickwork and paving.

Then there are several offerings by Fabritius; in addition to the two self-portraits that will already be familiar to visitors to the National Gallery, there is an intriguing small view of Delft, which appears to have been designed to be viewed curved, rather than flat, and through a peephole. The exhibition also provides a reproduction of this format. It strengthens the sense of place as you peer over the stringed instrument in the foreground and allow your eye to move from the stallholder on the left to the rising cobbles of the bridge on the right.

A sense of calm and well-ordered life also pervades the room devoted to architectural painting in Delft. This is the largest room in the exhibition, and it shows how adept a number of Delft artists were at painting grand interiors. Most of the views are of the two Delft churches, the Oude Kerk and the Nieuwe Kerk.

In many cases, dual perspectives are used instead of a single vanishing point. This is helpful in large images with more complex subject matter, where the eye travels distances to look at different components.

You feel you could reach out and feel the cool smooth polished stone of the pillars in Houckgeest's Interior of the Nieuwe Kerk, Delft, with the Tomb of William the Silent. In another image of the same church, you can admire the way that coloured light from the windows shines on to one of these pillars.

Taken as a whole, this is a big exhibition packed into a relatively small space. It is likely to be very popular, and despite ticket allocations and extended opening hours, you are going to have to spend time admiring your fellow visitors’ hairstyles at close quarters before you get near the smaller pictures.

But it's worth it. The case for presenting Delft as a centre for artistic excellence is resoundingly proven. The best of the Van Vliets, Houckgeest, de Hooch and Fabritius are manifestly superior to the second-string Vermeers, but the best works here are the works of Vermeer.